- National

- Tiger Zinda Hai in Gujarat: Know How It Vanished in the Past

Tiger Zinda Hai in Gujarat: Know How It Vanished in the Past

In the lush, undulating landscapes of Gujarat's Ratanmahal Wildlife Sanctuary, a remarkable story is unfolding. A male Bengal tiger, a four-year-old wanderer from Madhya Pradesh, has made this sanctuary his home for the past nine months since February 2025.

Captured on camera traps drinking from a man-made waterhole amidst dense teak forests, this solitary predator marks the first confirmed tiger presence in Gujarat in over three decades. Once a thriving habitat for the majestic Bengal tiger, Gujarat lost this iconic species to human pressures, only to witness its tentative return today.

How did the tiger vanish from these lands? What has spurred its reappearance? And what steps must Gujarat take to secure its future? This article delves into the past, present, and potential future of tigers in Gujarat.

The Decline: How Tigers Vanished from Gujarat

Gujarat’s forests once echoed with the roars of Bengal tigers, their presence documented across districts like Dangs, Narmada, Sabarkantha, and Bharuch until the mid-20th century. Historical accounts suggest a population of around 50 tigers thrived here in the 1950s and 1960s, coexisting with leopards, and a rich prey base of chital, sambar, and wild boar.

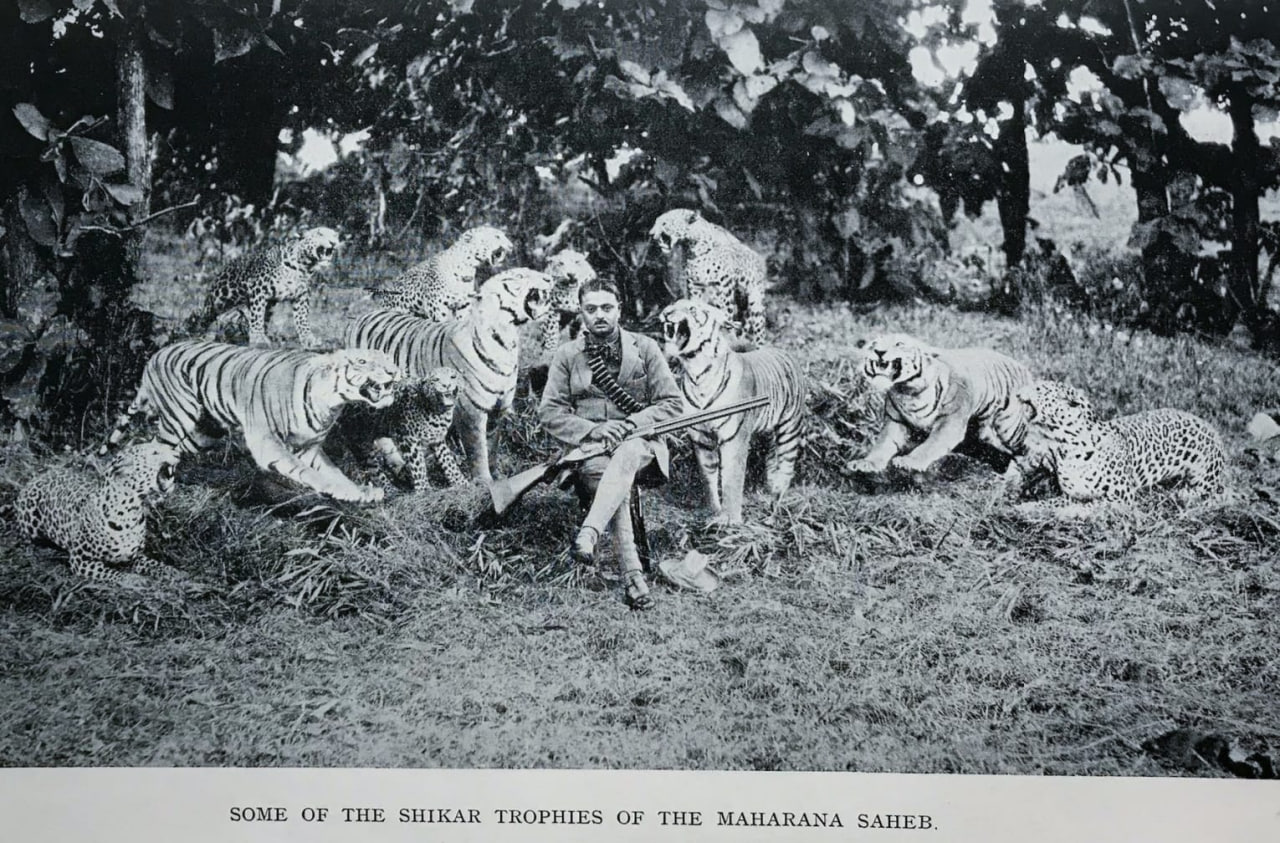

However, this ecological harmony unraveled due to relentless human activity. Poaching surged in the late 20th century, with the last recorded tiger killed by poachers in Waghai, Dangs, in 1983. The demand for tiger pelts, bones, and trophies decimated their numbers, while habitat loss from deforestation for agriculture, dams, and settlements fragmented their roaming grounds.

The prey base collapsed as overhunting and encroachment reduced herbivore populations, forcing tigers into human areas where they faced retaliation or starvation. By 1989, Gujarat’s forest department officially declared tigers extinct, a status reaffirmed by the 1992 census and the 2001 national tiger estimation.

Occasional transients, like a tiger that died of starvation in Mahisagar in 2019 after a two-week stay, highlighted the inhospitable conditions. The tiger’s exit left a void, turning Gujarat into a land of lions and leopards, with its striped legacy fading into memory.

The Return: A Tiger Reclaims Ratanmahal

The tide began to turn in February 2025 when a young male tiger crossed from Madhya Pradesh into Ratanmahal Wildlife Sanctuary, a 56-square-kilometer haven straddling the Gujarat-Madhya Pradesh border. Driven by Madhya Pradesh’s booming tiger population—over 785 as per the latest estimates—and lured by Ratanmahal’s reviving ecosystem, this tiger has stayed, hunting and marking territory. Camera traps, first triggered on February 23, 2025, show him thriving, a testament to the sanctuary’s improved prey base of chital and nilgai, bolstered by afforestation and water conservation efforts over the years.

This natural migration, facilitated by the Vindhyachal corridor, underscores a success story of regional conservation. Gujarat Forest Minister Arjun Modhwadia hailed it as a “historic moment,” noting that the state now hosts three big cats: the Asiatic lion (over 600 in Gir), the leopard, and the tiger.

The forest department has reinforced the area with herbivore relocations and advanced monitoring, ensuring the tiger’s safety while minimizing human interference. This return is no fluke but a ripple effect of India’s Project Tiger, which has restored tiger habitats elsewhere, pushing young males to seek new territories.

The Future: Opportunities and Challenges Ahead

The tiger’s nine-month residency in Ratanmahal signals a potential renaissance. Conservationists estimate that introducing a female tiger could spark a breeding population, possibly reaching 10-20 tigers in a decade if habitats expand. The National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) is considering Ratanmahal for its “Tigers Outside Tiger Reserves” (TOTR) program, which could unlock funds for corridor development and protection.

With Project Cheetah underway in Kutch’s Banni Grasslands, Gujarat could soon be the only state to host all four big cats, boosting its global conservation stature and ecotourism potential.Yet, challenges loom. Climate change could dry water sources, while an influx of dispersing tigers from Madhya Pradesh might strain resources or spark conflicts.

Human-tiger encounters in Dahod’s fringe villages, where livestock losses could breed resentment, pose a real threat. Unregulated tourism, if not managed, could disrupt the tiger’s habitat, as seen with Gir’s lion tourism pressures. The future hinges on balancing growth with preservation—success could mean a thriving tiger meta-population across state borders, while failure risks another extinction.

A Call to Action: What Gujarat Must Do

To cement this revival, Gujarat must act decisively.

1.First, strengthen the prey base: Accelerate translocations of chital from Gir and sambar from Madhya Pradesh, while curbing overgrazing in buffer zones. Ratanmahal’s recovery proves this strategy works.

2. Second, protect corridors: Collaborate with Madhya Pradesh to widen the Vindhyachal corridor, planting native species and using drones and AI traps for surveillance, as successfully implemented in Gir.

3. Third, mitigate human-wildlife conflict: Introduce eco-development initiatives—honey farming or ecotourism homestays—to reduce forest dependency, and offer compensation for livestock losses, a model proven with lions.

4. Finally, elevate Ratanmahal’s status: Pursue national park designation to secure funding and stricter protections, while capping tourist numbers to avoid ecological strain. Integrate it into Project Tiger’s network for expert training and anti-poaching support. With PM Narendra Modi’s vision and the forest department’s dedication, Gujarat can transform this lone tiger’s return into a legacy. The stripes are back—now, it’s time to ensure they stay.

About The Author

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book. It has survived not only five centuries, but also the leap into electronic typesetting, remaining essentially unchanged. It was popularised in the 1960s with the release of Letraset sheets containing Lorem Ipsum passages, and more recently with desktop publishing software like Aldus PageMaker including versions of Lorem Ipsum.

1.jpg)